I. Introduction

There are many reasons for maintaining inventories, which may include guaranteeing the ability to meet short delivery times, ensuring availability of high demand products, optimizing production runs, and keeping new products poised for release on the market, etc. In recent times the context of companies, especially with regard to supply chains, has become increasingly complex, as companies strive to offer more and more varied products while providing innovative new options to consumers or special promotions on existing products. Moreover, the demands of service channels and the ongoing quest to lower overhead contribute to this complex scenario.

The great challenge is to achieve desired results consistently using the capacities and limited resources available, always with an eye toward fulfilling or, better yet, surpassing client expectations. In this way, finding opportunities for enhancing efficiency all along the value chain has become a key competence that all companies must master.

It is not news to anyone that this shall require an integrated approach to how we conceive and organize the several links in the supply chain, especially with regard to inventory planning, volumes and diversity, location and how products are moved to the greatest advantage.

II. Operational Strategy – A key element of profitability

Whether the commercial or operations area should have priority is a common question that arises in many companies. Of course, the correct approach is to prioritize both; though everyone knows that one area comes before the other. The commercial area must grasp the needs and expectations of the market so that it can establish value proposals targeted to diverse client segments in line with strategic business objectives. It should be mentioned that a value proposal entails the company’s positioning attained by a mix of products, sales conditions and its experience serving these segments. This set of commitments and client service functions must always strive to optimize the company’s profitability; and it should be a kind of template for the operations area to follow for defining its planning, organization and implementation strategies.

If the operations strategy is established and implemented properly, it can in the first instance serve to underpin the profitability of the company as it fulfills the value proposal in the marketplace. In addition to this, an operations strategy that optimizes the mix, location and flow of inventories helps the company achieve the value proposal in a more profitable way. It is quite easy to fulfill client requirements and offer high levels of service by keeping bloated inventories of all products at every possible location in the supply chain, provided the company shareholders are not too demanding about returns on their capital investment. Since this scenario in not very likely, logistics directors and managers become key players in optimizing the investments made in the area of inventory management.

Occasionally, the organization tries to turn the competitive advantages of its supply chain into one of its “core competencies”, enunciating it in a formal conceptual “statement” informing the strategic driver of the business, from the general sphere; i.e., how to accomplish delivery of services and geographic coverage, with agility and flexibility, while avoiding undue overhead; to the specifics of how to develop the capacity to carry off the launch of large quantities of new products every year.

The important thing to understand is that not everything can be done, not everything can be improved. To do so would be too expensive. Companies must allocate resources to those things that best serve the goals and interest of the business. Ultimately, it is a question of optimizing company resources with profitability always at the forefront.

III. Defining the operations strategy

Based upon the strategic drivers established by the executive director, the operations strategy is the formal statement of how the company strives to ensure its supply chain meets client requirements. In other words, it provides the guidelines for organizing and operating the supply chain to ensure fulfillment of the value proposal in the most profitable way. Without an operations strategy, the supply chain would be bereft of a formal structure, plan or implementation method for optimizing results both locally and globally. This integration needs to be carried out in all possible ways: area by area, location by location, and in view of both clients and providers.

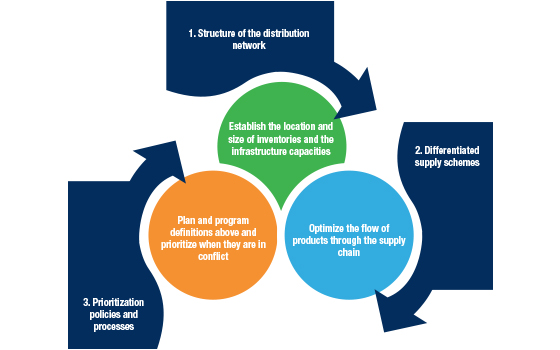

The operations strategy consists of three key elements: a) distribution network structure; b) supply schemes; and c) prioritization policies and processes.

Each of these elements is described below:

a) The structure of the distribution network

The first group of definitions is the most important in terms of how the company will invest in the supply chain assets. The service requirements, especially the response time expected by the client at the end of the chain, shall determine the structure of the network capacities in such a way that each link in the chain works harmoniously with its internal client, thereby allowing the entire supply chain to fulfill the conditions of the service offered to the end client. The main elements to consider are the structure of the network, i.e., establishing the location of production plants, distribution centers; and the infrastructure capacities of plants, warehouse/distribution centers, including investment in the distribution fleet, both owned and hired.

b) Supply schemes

If the differentiated value proposals are defined correctly, they will be based upon the fact that the diverse products and clients do not contribute to the company’s profitability in the same way. In this light and in view that products with distinct demand and supply limitations need to be handled differently, any effort to design and implement improved inventory management must implement appropriately differentiated schemes for each product. The purpose of differentiation in the schemes and processes is to optimize the relationship between the uses of resources in the chain, the cost of maintaining the chain, and the service to internal and external clients. This optimization must always strive for one thing: maximization of the profitability of the company.

To implement the operations strategy, companies must build mechanisms so that planning, tactical and execution efforts are aligned with the entire supply chain. To this end, inventory planning should be informed by the following two basic concepts:

1. Establishment of differentiated service objectives:

As mentioned above, the starting point for structuring and aligning the supply chain rests upon the definition of differentiated value proposals. Moreover, the operations strategy must address the commitments it assumes and clearly states these in attainable service objectives that ensure alignment of the supply chain with the value proposal.

Generally, these service objectives must be differentiated by channel, client, product type (ABC classification), etc., in such a way that, while upholding the value proposal to clients, they also underpin the organization’s earnings. Depending on the specific proposal, these service objectives are generally defined in terms of delivery times and volumes fulfilled.

As is the case for all points in the strategy, the idea is to create mechanisms to apply leverage in order to spread the Planning and Implementation Criteria and Policies systematically throughout the supply chain, which in turn are aligned with business objectives set by the executive director. In this case, establishing the differentiated service objectives, which obviously must be implemented by means of the supply schemes and processes, will allow the organization to do several things: on one hand, it can standardize planning throughout the supply chain; and, on the other, it provides resource deployment modeling tools for the central planning area, allowing assessment of the impact of diverse scenarios on the operational area (e.g., warehouse use, stock volumes) and on financial consequences (e.g., inventory rotation, service levels, lost sales, etc.).

The benefit of establishing these mechanisms is derived from having responsive levers at one’s disposal, which can be moved to optimize results throughout the supply chain. It should be stressed that this is implemented by means of schemes, processes and IT tools.

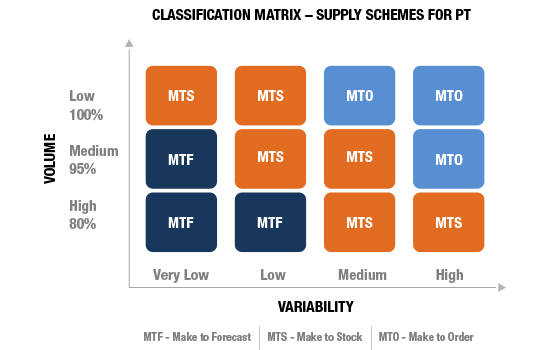

2. Defining differentiated supply schemes:

The selection of the supply scheme to use for each of the products at diverse points along the supply chain depends on three factors: 1) the product’s demand characteristics; 2) the supply capacities; and 3) the internal and end client service objectives or expectations.

In light of product classification (on the basis not only of demand, but also on factors such as product category, market segment, etc.), and for a specific point along the chain, planning and operations schemes are applied to move the product in accord with the most reliable signals at any given time. The first thing to consider is the planning of product movements (when to order, when to produce or when to transfer from one point to another) as a function of expected or future demand, which allows planners to anticipate demand levels and trends, and proactively prepare the supply chain structure. This is known as a “Push” scheme, and it is usually underpinned by the use of accurate demand projections.

When accurate predictions of demand are not possible, it is very risky to implement a “Push” scheme, because one might plan on mistaken demand assumptions that would inevitably lead to either undersupply or cumbersome oversupply. In these cases, a “Pull” scheme is recommended, which instead of trying to anticipate demand, simply waits for inventory levels to reach a trigger, set on the basis of recent demand at that point in the supply chain, before products are moved. Such a scheme is by its very nature reactive, but it still allows inventory levels to be modified ahead of significant shifts in projected demand in the short and medium terms.

Finally, there is another scheme for moving products along the supply chain which is known as “Make to Order”. This scheme is usually used for low-demand products or those that are ordered only sporadically. Production of these goods often entails special raw materials or expensive manufacturing processes. As such, keeping these products in stock would be very costly indeed. These products are purchased, produced and distributed only after the client has placed an order.

c) Alignment of planning and implementation processes with prioritization of policies

The planning and implementation processes activate the required differentiated supply schemes. Moreover, by means of the way the areas involved are integrated, synchronized and aligned, these processes must ensure adaptation of the structure of the supply chain throughout the year. For example, if the strategy sets differentiated service level objectives based on ABC classification, the planning processes should ensure periodic review and updating of this classification throughout the supply chain. Failure to do so would mean the strategy is not fulfilled.

Inventory planning is a part of global tactical planning of the supply chain. As such, it must be properly woven into the set of planning activities in order to ensure the entire supply chain is prepared to meet projected demands in coming seasons. This presupposes that inventory planning must be synchronized with the sales and operations planning (S&OP), as well as being aligned with market cycles. Since demand projections are a key input for executing inventory planning, the frequency of inventory planning processes must be enunciated. This period, moreover, must be aligned with the demand projection. If a new demand projection is forthcoming every three months, the inventory planning must be done at least as often.

Additionally, the “speed” of the market in question must also be considered; i.e., if the demand in SKU does not change from month to month, but rather is more seasonally responsive or simply flat throughout the year, then it will not be necessary to update the inventory planning nearly as often. Under these scenarios, inventory planning can be linked to demand planning, as mentioned earlier. On the other hand, when demand in the market in question is more changeable, when there are special marketing campaigns and promotions, or when products are pulled or new products launched in each sales season, inventory planning needs to be updated more often than the demand planning.

Finally, one must take into account certain institutional policies that might be adopted to align/standardize the way in which decisions are made all along the supply chain. These decisions made by organization personnel, and which may or may not be supported by formal processes, must conform to the established supply strategy. In the final analysis, it in neither possible nor desirable to override the criteria of decision makers, but it is necessary to document the guidelines to be followed for reaching decisions. For example, it is useful to establish the criteria for prioritizing product orders when supply is limited. These policies can also be applied in the area of assigning production capacity on the production line and for allocating provisions of common raw materials.

IV. Conclusions

The challenges faced by company planning and logistics areas are increasingly complex and entail nothing less than the global management of resources and capacities in the supply chain with an eye to controlling spending, fulfilling expectations, and responding faster to the changing needs of clients and the organization’s internal initiatives.

The only way to achieve this is by aligning each and every link in the chain by means of an operations strategy that is both properly conceived and practically feasible. With regard to inventory planning, the key is to work with differentiated service objectives that contemplate appropriate supply schemes underpinned by implementation and planning processes aligned with the tactical planning of the entire supply chain.

About Sintec

Sintec is the leading consulting firm focused on generating profitable growth and developing competitive advantages through the design and execution of holistic and innovative Customer and Operations Strategies. Sintec provides a thorough and unique methodology for the development of organizational competencies, based on three key elements: Organization, Processes and IT. Furthermore, Sintec has successfully carried out more than 300 projects on Commercial Strategies, Operations and IT issues with more than 100 companies in 14 countries throughout Latin America. Our track record of more than 25 years makes Sintec the most experienced consulting firm in this area of expertise in the region.

Mexico City: +52 (55) 5002 5444

Monterrey: +52 (81) 1001 8570

Bogota: +57 (1) 379 4343

Sao Paulo: +55 (11) 3443 7433