It happened in a company…

“We have several Board Meetings with the same topic,” mentions one of the directors, “the growth we are achieving in sales and gross contribution is not reflected in the operating profit of the company and we still don’t have a clear answer as to what we do.”

The Director General replied: “As I have mentioned in the past, our strategy is focused on increasing revenues, which have we definitely achieved. Volume growth will bring us economies of scale, which will result in greater overall profitability for the company. Here’s how it works; growth first, profits later. You’ll see in three months, at the next Board meeting, how the results are going to appear.”

“Well, I’ll be here for them,” said the Board Member, incredulously.

Situations and discussions like this are very common. Unfortunately, it continues to be a conversation that lasts without a mutual understanding of the factors involved in the situation. In the case of the Director General, he gains some time without really knowing if his promises are viable; on the other hand, the Board Member, not having enough information or more detailed analysis, cannot intervene beyond demanding that a result is provided.

This article will demonstrate why the growth in sales and gross contribution does not necessarily translate into higher operating profitability for the company and the causes of this misalignment are highlighted. An understanding will definitely shed light on the type of actions a company must take to move from sales growth to profitability growth.

The problem

Common thinking among executives is that the growth of the company will automatically translate into greater profitability. The logic is that if the volume grows, costs will remain the same and therefore, the profitability of the company will grow. However, in practice this is very different.

In many cases, the company grows but profits don’t grow at the same pace. Obviously, profitability also does not grow at the same pace in terms of return on assets. The situation is that the costs, both fixed and variable, increase so that the growth in the gross contribution of the company is not reflected in operating income.

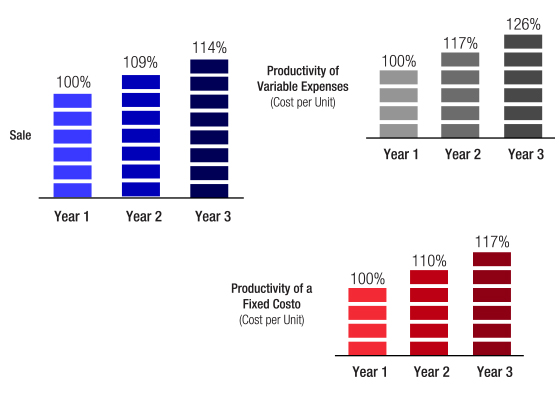

FIG. 1 Represents the fixed and variable costs per unit, two years apart, of a company. The phenomenon we describe is clear upon seeing the expenses of the company: a 14% increase in sales volume does not cause fixed and variable costs per unit to decrease, but on the contrary, they increase! The productivity in costs associated with higher volume does not exist.

There are four main causes of the above: a piecemeal approach, incorrect measurements, insufficient management and the cost of complexity. We will review each one.

Partial approach

The first sin is committed by an executive when focusing on growing the company through revenue (sales) without placing the same level of attention on profitability. The goal of an executive should be to drive profitable business growth, not just growth. However, it seems that this is not clear to all executives, especially to those who think that the value of their business depends on its revenues and not its ability to generate profitability.

In the process of growing, they seek to move more product volume. In this logic, there is nothing more expensive than a lost sale, therefore at all cost – and expense!- resources are assigned, raw materials turnover quickly; they are produced with overtime; month end sales are pushed; customers with very low or zero returns are captured; and even months of over 31 days are created, among other things. In the end it is a matter of approach that permeates throughout the organization because its people no longer skimp on costs or expenses. They think selling is above all.

When an executive makes a pronouncement in relation to an objective, it has an amplifying effect on an organization. Therefore, when a director says that the growth is fundamental, he pronounces on the matter and makes decisions on the matter: this is interpreted in the world of the organization as “one must sell by any means.” That statement gives people the equivalent of a license to kill.

Each person controls resources, from an operator to an executive, who with their decisions and actions, have effects on the expenses and costs of the company. A manifesto for growth generates a signal that goes to the entire organization, indicating that it is more important to sell than how resources are used, and this leads to bad decisions, wrong interpretations and more expenses. In the sin, there is the penance. It’s that simple.

Incorrect measurements

A critical issue is the measurements we use to manage and evaluate staff. Companies are dominated by financial measurements and leave aside the operational measurements that can hide performance issues. An error of this type is to measure the costs as a percentage of revenues. Financially, it is correct, but operationally it is a serious error. This simple fact can hide many operational problems of the company, causing inefficiencies and non-value added costs. Why? Simply because income is affected by prices, which may bear little relationship to costs. For example, why measure the logistics cost as a percentage of the sale? What a supply chain moves are boxes, liters, kilos, units … What does one have to do with the other? Nothing.

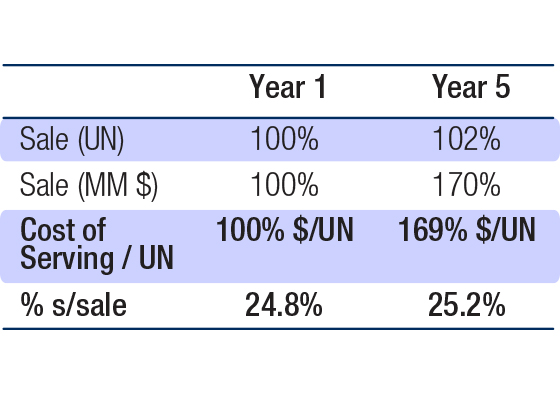

In Fig. 2, a company is presented with 5 years of difference, where the cost of serving (logistic expenses + sales) as a percentage of income has not gone up. With this information, we could ensure that productivity is maintained; however, the cost per unit increased by 69% in 5 years, indicating a loss of productivity.

Two completely opposite statements of the same phenomenon are caused by the lens through which one looks. If we just focus on the financial measurement, no signs of trouble will be found, it would seem that the company is relatively okay and, therefore, no major actions are required. On the other hand, when measuring cost / unit, it is clear that unit costs have increased significantly, revealing a problem that we must attack.

Management

Growth is chaotic by nature and things can get somewhat out of control. If we add that the company does not have good management, it becomes the perfect formula for chaos to be amplified and results in higher costs.

What kind of management is correct? Basic management will work. Goals, plans and actions must be established, as well as monitoring, detecting problems early and correcting them before growth turns them into a crisis. Management of simple business variables: costs, inventory, waste, portfolio, deliveries, etc. Nothing special at all, but without that control, the growth dream can quickly turn into a nightmare.

Inappropriate management creates cracks along the value chain, allowing resources to escape as a series of leaks in a pipeline, allowing much of the profitability of the company to escape.

Cost of complexity

The addition of new customer segments, the widest range of products and competitive dynamics have resulted in value chains which are more difficult to integrate and execute; therefore more complicated in their administration. The main mistake is to assume that for the value chain, from vendors to suppliers, it is marginal to add new customers and products, which is what generates growth.

When a company launches a new product and / or conquers a new client, it triggers a series of events backwards through the entire chain. To the extent that these products and customers have different behavior than that which the company handles, then different activities will be required: different forms of buying, selling, producing, storing, transportation, and even checking products. This generates costs that are not marginal.

Figure 3 shows the behavior of costs as products are added. We can note how there are products whose marginal costs rise in a non-marginal way, this is due to the behavior of this category of items in the store, that is, the labor required for assembling orders as well as more space for inventory. Besides, the marginal contribution of these products don’t match their cost contribution.

What happens in the stores can occur throughout the value chain of the company. When adding products, the costs will not be marginal, resulting in lost productivity and profitability. The first step for resolving this problem is to understand the cause-effect of the complexity of the chain, allocate costs appropriately to prevent some products from subsidizing others, and better measure the performance of the items.

But the most important part is that companies must develop their skills throughout the value chain to minimize the impact of costs. This requires competencies related to different models, different processes, including different organizational structures.

Conclusions

It is not a valid assumption that growth will automatically bring profitability, although many executives still believe this. Companies can grow profitable by improving their indicators and operational management and maintaining the focus on profitability- not just on revenue-and develop skills to minimize the impact of the costs of the complexity that growth generates.